Leonard Martin: Painting to the Rhythm of a CitY

In New Orleans, artist Leonard Martin followed the movement of Carnival the way one follows a river. An experience of the city, of history and of the collective that profoundly transformed his way of painting, now on view at Galerie Templon in Paris.

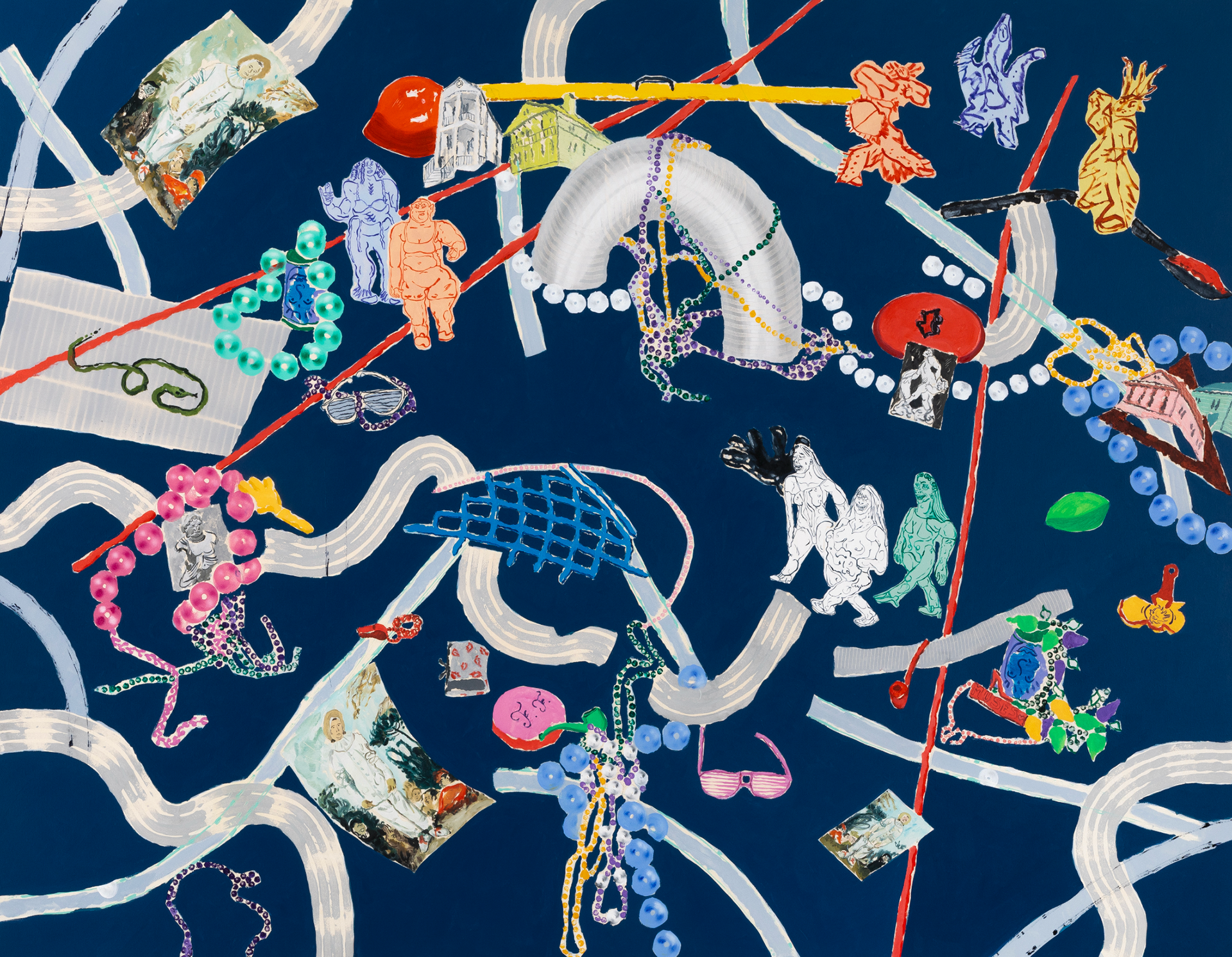

A painter of fragments and displacement, Leonard Martin builds a body of work in which images circulate, collide, and recombine like open-ended narratives. Drawing as much from art history as from popular culture, his painting advances through montage, clues, and successive shifts, refusing any single, fixed reading. His works, currently presented at Galerie Templon in Paris, question how we inhabit the contemporary world: a fractured, unstable world, crossed by contradictory memories.

Invited in residence to New Orleans by Villa Albertine, Leonard Martin immersed himself in the experience of Carnival, from Mardi Gras to the slow, uninterrupted parades that flow through the city like a river. There, he collected objects, observed gestures, scrutinized rituals: throwing, waiting, celebration, loss. From bead necklaces to Harlequin figures, his images bear witness to a city where celebration coexists with catastrophe, where collective memory is endlessly replayed between mask and revelation.

In this interview, Leonard Martin looks back on this decisive immersion, on the way a city tells its story, and on what Carnival taught him: leaving the protected frame of the studio, allowing oneself to be carried along by the procession, and painting from a fragile viewpoint, at the level of objects, at the level of childhood, where the world begins to speak before words.

Your residency in New Orleans with Villa Albertine immersed you in the heart of Carnival. What struck you most upon arriving: the music, the costumes, the crowd, or the excess of all of it at once?

I was struck by the continuous movement of the parades, advancing slowly but without interruption. It’s a momentum that comes from far away, with great force and long reach, like a river. And precisely, the spectators stand on the banks with folding chairs, coolers, nets and step stools to catch the objects thrown from the floats. This gesture of throwing fascinates me: the outstretched arm hoping to be chosen, the object flying off, sometimes without a recipient. There’s a possible metaphor for our world and our society. Why want to be noticed and obtain something at all costs? Where to go? Where to land?

Carnival is at once a celebration, a mask, and a collective memory. What did New Orleans teach you about the way a city tells its history?

I was impressed by the awareness its inhabitants have of their history and collective memory. Many know the house where a particular musician or recognized figure once lived. People in New Orleans, and in Louisiana more broadly, readily share historical anecdotes or genealogical connections. This history is very rich, but also deeply painful, and Carnival may be a possible place for repair. In this pure expenditure of the thrown object, there is perhaps an emancipatory gesture that dismisses fate.

You collected fragments, objects, everyday images. If you had to choose a totem object to sum up this residency, what would it be?

Without any doubt, the bead necklace. To me, it represents all these communities that coexist and parade together during Carnival but are held by a link that could break at any moment. The slightest political jolt can undo this fragile balance. There is also a very strong contradiction in this object, bringing together celebration and catastrophe. The beads scatter throughout the city and even into the waters they pollute. New Orleans stands on the front line of the climatic and ecological questions threatening our world.

Mardi Gras is often associated with joy, but also with a complex social and political history. How do these contradictions feed into your work?

My own memory as a spectator merged with what I discovered there. Images never arrive alone but in constellations. I placed clues in my paintings, references to works well known. It is impossible to forget that Western painting emerged at a time when Europe dominated the rest of the world. And Carnival constantly masks and reveals that history. I think of those beads that entered the Caribbean world through the triangular trade. Today, they are manufactured in Chinese factories.

You often use montage, collage, and fragmentation. Is this a way of speaking about the world as it is today: fragmented, unstable, multiple?

It is certainly a symptom of our contemporary experience. But I find in this dispersal many promises of meaning and form. Leaving behind the single, elevated viewpoint of the still life allowed me to travel within the image. By placing myself at the level of objects, I can look from the perspective of childhood. That is, something prior to language, something emerging, where the clash of the world already resonates.

The Harlequin costume recurs in your work as a central figure. Is it a character, a disguised self-portrait, or a metaphor for our time?

Even if I don’t reference it directly, Harlequin carries patched-together fragments of a historical narrative that must constantly be rewritten. It is of course an alter ego of the artist, bound to this inheritance but with limited means. There is Watteau’s Gilles with his large white canvas and the others in the background mocking him. But at New Orleans Carnival, the Harlequin costume evokes for me creolization as a breath of fresh air and a possible path toward repair.

After New Orleans, what does a city represent for you: a backdrop, a playground, a character?

Thanks to New Orleans, I moved beyond backdrop and playground to enter history. Carnival is far more than a host setting. The procession carries you along without asking your opinion. Leaving the protected frame of the studio was a great stroke of luck for me.

New Orleans is a city marked by catastrophe, but also by an incredible capacity to celebrate. Does that energy find its way into your way of working?

New Orleans shatters many certainties. I was in the process of painting small colorful houses cut out of paper. I thought I was naively suspending them in a cluster of objects, but once painted, I thought of the storm at the beginning of The Wizard of Oz, where the house flies through the clouds. It was the twentieth anniversary of Katrina.

If you had to paint the soul of New Orleans using only three colors, which would you choose, and why?

Purple like hair.

Green like a scale.

Gold like a breath.

Green like a scale.

Gold like a breath.

Finally, if you could parade in another city at the next Mardi Gras, which would it be, and in what costume?

Dunkirk, as a herring.

« Chef Menteur », until March 14 at Galerie Templon, in Paris. Templon.com

Photos by Laurent Edeline

GALLERY

Léonard Martin, Parade Tracker III, 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas 171×219cm—671/4 ×861/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Léonard Martin, Parade Tracker II, 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Léonard Martin, Chef Menteur II, 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.

Léonard Martin, Beads & Bodies VII, 2025, oil and acrylic on canvas Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York.