Ken Nwadiogbu: Memory in Fragments, Identity in Layers

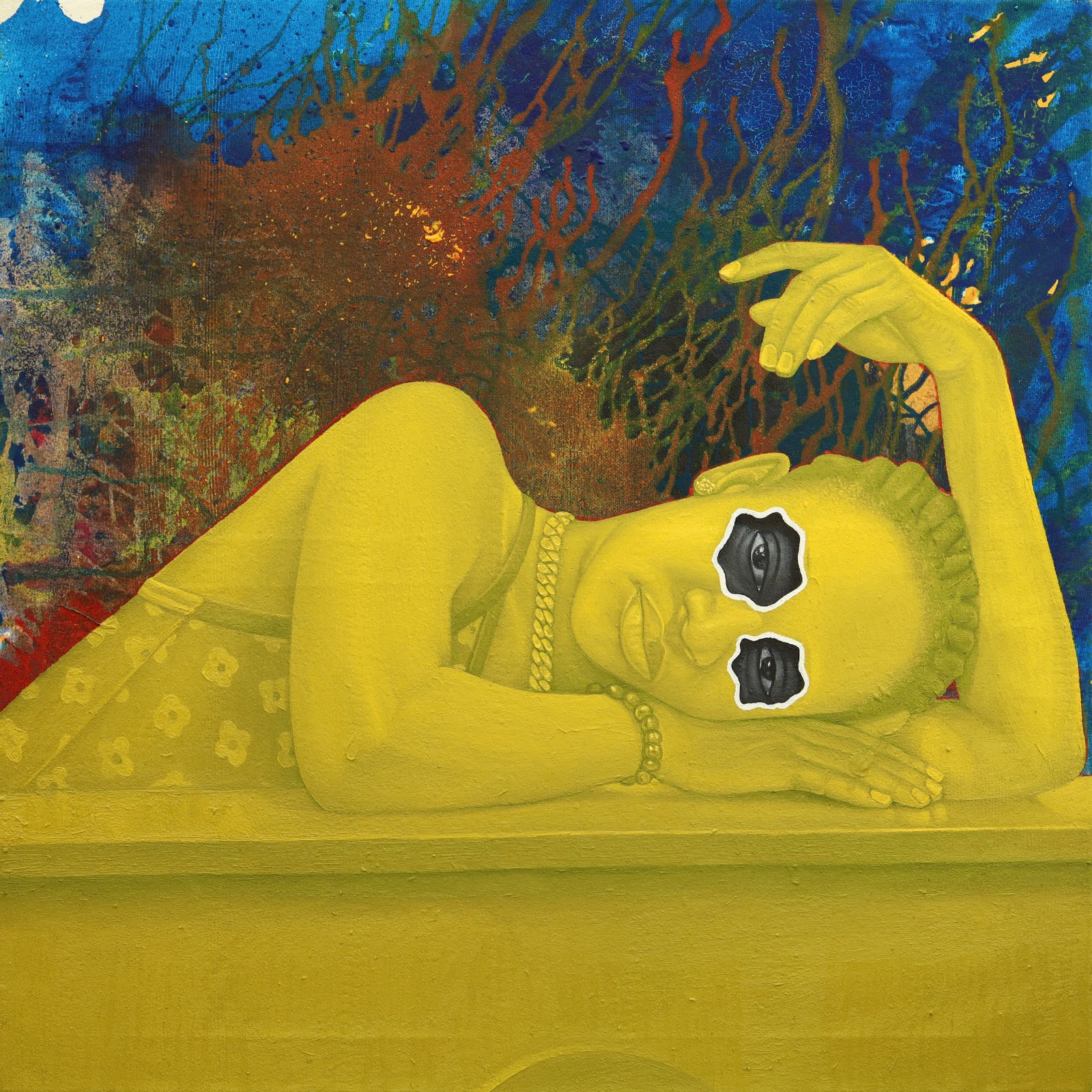

This summer, Nigerian artist Ken Nwadiogbu presents a major solo exhibition in London, offering new works that push the boundaries of figuration, memory, and black identity. Known for his hyperrealistic yet conceptually rich portraits, often marked by cut-out gazes, fragmented figures, and layered storytelling, Ken Nwadiogbu belongs to a generation of Nigerian artists rewriting the visual narrative of Africa through deeply personal, politically conscious work. Initially trained as a civil engineer, he is entirely self-taught, and entirely unafraid to experiment. His art is bold, quiet, haunting, and alive with questions. In this conversation, Ken Nwadiogbu reflects on Lagos, where he was born, but also resistance, memory, collaboration, and the many selves that live beneath the surface of his canvases.

You’re often described as a hyperrealist, but your work also breaks the frame of traditional realism. How did you find your voice as an artist?

I started with hyperrealism, yes. It was the first thing that caught my attention. I remember, back in university (I studied civil engineering at the University of Lagos) someone showed me a hyperrealistic painting. I was completely stunned. I couldn’t believe it was drawn by hand. That’s how the journey started. I wanted to learn how to do that, how to draw like that. But as I kept working, I started making mistakes. Beautiful mistakes. Accidents in the process. That’s when things started to change. My art began to shift. It became more conceptual, more layered, more surreal. I started asking: What is my own language? What is my voice? I realized I didn’t just want to replicate life. I wanted to reflect on it. And that’s when the real transformation began.

Many of your works are deeply concerned with identity, social justice, and the Black experience. Where does that come from?

Lagos. Growing up here means living with contradictions: beauty and struggle, noise and stillness, poverty and wealth. I’ve experienced them all. My work is born from that environment. I believe art should be truth. It should reflect the way of life. When I paint, I’m talking about what it feels like to be Nigerian, African, to live in a place that is constantly moving but doesn’t always move forward. There’s no archiving here. No one is really writing our stories. So I want my canvas to be a space of testimony. A record of now.

You often depict young people, especially youth in resistance. What do you want your audience to take from that?

Honestly? I used to care a lot about what people took from my work. I don’t anymore. Once the painting is finished, it doesn’t belong to me. It’s theirs. I want the viewer to feel something, whatever that is. Sadness, pride, confusion, curiosity. It’s all valid. That said, the work always comes from a place of awareness. I want it to start conversations: about power, injustice, freedom, identity. Especially for people like me. Young, African, often unseen.

Your compositions are often fragmented: faces obscured, bodies layered. Where does that visual language come from?

From memory. From how we remember. When you think about something from your past, you rarely remember the full picture. What you remember are fragments. Sometimes, those fragments are the most powerful parts of the story. Also, my life is layered. I was an engineer, now I’m an artist. I’ve lived in Lagos, I’ve lived in London. There are different versions of me: identities, experiences, influences. So when I’m painting, I’m also uncovering those layers. That fragmentation is personal. It’s not just a technique. It’s my life.

If I asked you to paint Lagos as a canvas, how would you describe it?

Lagos would be chaotic. Loud. Surreal. Nothing in proportion. Big hands, small faces, long legs. I’d use a lot of yellow, that’s the color of Lagos for me. The buses, the taxis, the heat. Even the sky feels yellow sometimes. The texture would be matte, not glossy. Because Lagos is raw. It’s real. You can’t polish it. I’d want the painting to feel like Lagos. Energetic, unpredictable, sometimes overwhelming. But alive.

You’ve said your mission is to "enlighten your society." How do you go about curating the themes of your work?

I try to create work that stimulates, intellectually and emotionally. That’s the foundation. I love reading philosophy, history, theory. But I’m also deeply grounded in the streets. I want people to come to the work and leave with something. A question. A thought. A new perspective. I also co-founded a project called Artists Connect Africa. It’s a space for young African artists to come together, connect, collaborate. We’re building a new kind of ecosystem, one that is supportive, creative, and rooted in African realities.

What artists, past or present, have inspired your evolution?

So many. Frank Bowling, first of all. His use of color, his philosophy, his calmness. Then Peter Doig: his landscapes are like dreams. Jean-Michel Basquiat, of course, for his energy and symbolism. In Nigeria, I’ve been influenced by Victor Ehikhamenor, Nengi Omoku, and many more. Some inspire me technically. Others conceptually. I study how they work, how they speak through color and form. I steal, shamelessly… But I steal to build something new.

You mentioned living between Lagos and London. How do these two cities feed your work?

London gives me space to think. To slow down. But Lagos gives me heat. Urgency. Tension. There’s no time to hesitate here. You just create. It’s exhausting but exciting. When I’m in London, I reflect. When I’m in Lagos, I react. Both are necessary.

What has surprised you the most about the reactions to your work?

That people feel it, deeply. I’ve had people cry. I’ve had people get angry. I’ve had people see something completely different from what I intended. And I love that. Because that’s what art should do. You make something, and then it takes on a life of its own. It’s a little scary. But it’s also beautiful.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

I hope I leave behind stories that mattered. That my work gave people permission to feel, to remember, to question, to imagine. And I hope I helped build something that lasts. Not just a name, but a space, a path, a future.

Ken Nwadiogbu’s solo exhibition Yellow Is the New Black opens on August 13, 2025 at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London (Tower Bridge), running through September 6, 2025. His latest body of work explores themes of identity, memory, and migration through richly layered, hyperrealist portraits. More info at kristinhjellegjerde.com

Photos by Morgan Otagburuagu

Originally published in CITY MAGAZINE INTERNATIONAL #1

GALLERY

Ken Nwadiogbu, How To Train Yourself To Fly, 2025

Ken Nwadiogbu, Waiting For You, 2025

Ken Nwadiogbu, In Pursuit Of Happiness, 2025

Ken Nwadiogbu, Beyond Reasonable Doubt, 2024