KEZIAH JONES: RYTHM IS UNIVERSAL

From the streets of London to the cafés of Paris, from Lagos to notebooks filled with fragments, riffs, and visions, Keziah Jones has always been in motion. The inventor of "Blufunk" (a genre where Yoruba rhythms collide with funk, blues, and jazz) the Nigerian-born musician is as much a poet of sound as he is a cartographer of cities, identities, and contradictions. For CITY, he opens up about rhythm as resistance, songwriting as ritual, and Lagos as a chord no one can quite resolve.

Your sound is famously hard to pin down: Blufunk, as you call it, blends funk, blues, rock, Yoruba percussion, and jazz. How did that hybrid sound emerge?

It really came from playing solo on the streets. When you're alone with a guitar, you have to be everything: the rhythm section, the bassline, the melody. Over time, I developed a style where all of that happens at once. That’s Blufunk. It was born in London and Paris, but it’s always carried Lagos in its bones, especially in the percussion. The rhythm is key. It’s the one thing that connects everything.

It really came from playing solo on the streets. When you're alone with a guitar, you have to be everything: the rhythm section, the bassline, the melody. Over time, I developed a style where all of that happens at once. That’s Blufunk. It was born in London and Paris, but it’s always carried Lagos in its bones, especially in the percussion. The rhythm is key. It’s the one thing that connects everything.

So rhythm comes first?

Always. Rhythm is universal. When everything else gets fragmented (identity, culture, language), rhythm still brings us together. It’s what unites.

Always. Rhythm is universal. When everything else gets fragmented (identity, culture, language), rhythm still brings us together. It’s what unites.

Your lyrics often reflect diasporic identity, social tensions, memory. Is songwriting a political act for you?

It’s more of a reflection than a statement. I write from my experience: growing up Nigerian, being educated in England, constantly moving. That gives you a fractured lens, but also a rich one. The question I keep coming back to is: what can unify us in the middle of all these contradictions? Again, rhythm is the answer.

It’s more of a reflection than a statement. I write from my experience: growing up Nigerian, being educated in England, constantly moving. That gives you a fractured lens, but also a rich one. The question I keep coming back to is: what can unify us in the middle of all these contradictions? Again, rhythm is the answer.

Can you describe your writing process?

It changes all the time. I’ve been writing in notebooks since I was twelve. I write down what’s around me: a color, a sound, a fleeting image. Later, when I find a riff or a groove, I return to those fragments and sometimes a song just… appears. But honestly, the best writing comes from doing nothing. Just sitting and waiting. If your mind has something to say, it will rise.

It changes all the time. I’ve been writing in notebooks since I was twelve. I write down what’s around me: a color, a sound, a fleeting image. Later, when I find a riff or a groove, I return to those fragments and sometimes a song just… appears. But honestly, the best writing comes from doing nothing. Just sitting and waiting. If your mind has something to say, it will rise.

You’ve seen several generations of African and diaspora musicians come up. What do you make of the new wave?

I love that they’ve taken ownership. Back in the day, you had to spend decades learning your instrument, then deal with record labels and all that machinery. Today, young artists represent themselves: they control their image, their business. That’s powerful. But my advice is this: use your music to uplift. Not everything has to be serious, but the music that really lasts, that changes things, carries some truth. That’s what soul is.

I love that they’ve taken ownership. Back in the day, you had to spend decades learning your instrument, then deal with record labels and all that machinery. Today, young artists represent themselves: they control their image, their business. That’s powerful. But my advice is this: use your music to uplift. Not everything has to be serious, but the music that really lasts, that changes things, carries some truth. That’s what soul is.

You’ve mentioned artists like John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Curtis Mayfield. Do you still feel part of that lineage?

Absolutely. Those artists weren’t just playing music: they were offering commentary, channeling resistance. We absorb music together. It seeps into our psyche. It shapes the way we walk through the world.

Absolutely. Those artists weren’t just playing music: they were offering commentary, channeling resistance. We absorb music together. It seeps into our psyche. It shapes the way we walk through the world.

You also draw inspiration from literature. Which writers have marked you most?

Bukowski, for his rawness. Murakami, for the quiet magic. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, obviously, and Dambudzo Marechera. Marechera was wild. He lived the fracture he wrote about. Right now, I’m reading Akala. He dissects class, race, empire. That speaks to me. I had to deconstruct all of that in myself too, being Nigerian, schooled in Britain, taught to see the world through a British lens.

Bukowski, for his rawness. Murakami, for the quiet magic. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, obviously, and Dambudzo Marechera. Marechera was wild. He lived the fracture he wrote about. Right now, I’m reading Akala. He dissects class, race, empire. That speaks to me. I had to deconstruct all of that in myself too, being Nigerian, schooled in Britain, taught to see the world through a British lens.

Three cities keep coming up in your work: Lagos, London, Paris. What do they mean to you?

London is where I first played, where I learned the street as a stage. Paris gave me space to reflect. But Lagos… Lagos is home. It’s intense, dissonant, beautiful, brutal. If it were a guitar chord, it would be one of those strange ones: partly harmonious, partly jarring. That is Lagos: you love it and you survive it at the same time.

London is where I first played, where I learned the street as a stage. Paris gave me space to reflect. But Lagos… Lagos is home. It’s intense, dissonant, beautiful, brutal. If it were a guitar chord, it would be one of those strange ones: partly harmonious, partly jarring. That is Lagos: you love it and you survive it at the same time.

Following the release of his album Alive & Kicking earlier this year, Keziah Jones is hitting the road in France for a summer tour:

July 10: Jazz à Juan Festival, Juan-les-Pins

July 15: Théâtre Antique, Vienne

July 20: Les Vieilles Charrues Festival, Carhaix

July 25: Théâtre de la Mer, Sète

July 30: Musilac Festival, Aix-les-Bains

July 10: Jazz à Juan Festival, Juan-les-Pins

July 15: Théâtre Antique, Vienne

July 20: Les Vieilles Charrues Festival, Carhaix

July 25: Théâtre de la Mer, Sète

July 30: Musilac Festival, Aix-les-Bains

Originally published in CITY MAGAZINE INTERNATIONAL #1

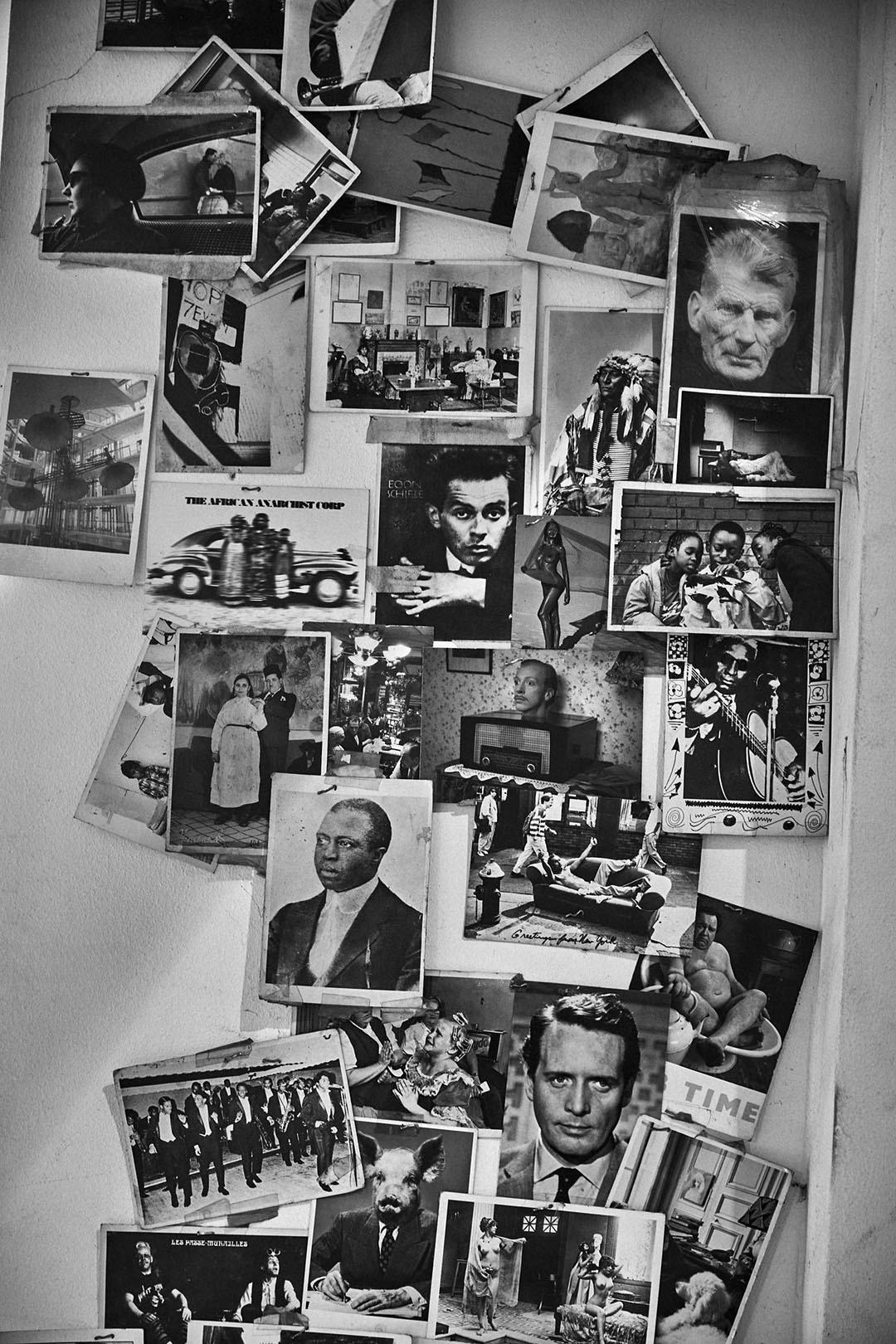

INSIDE KEZIAH'S HOUSE